It’s a zoo filled with animals! What’s not to like?

We first played Coloretto some time ago when I expressed interest in Zooloretto. Sean however insisted that playing the original Coloretto would be sufficient to cover the essence of both games and the newer and bigger one simply added a ton of extraneous stuff that doesn’t fundamentally change the game. So we duly played the older, found it okay but unspectacular, and like almost all filler games, quickly forgot about it.

We recently got a chance to play Zooloretto when Chee Wee had more free time to join us in our boardgame evenings and despite Sean’s reluctance to play it. All in all, we enjoyed it and liked it quite a bit more than Coloretto because it’s nice to have a solid theme and playing with animal tiles is more fun than playing with abstract cards. But Sean is still right that the core gameplay remains the same. My thoughts:

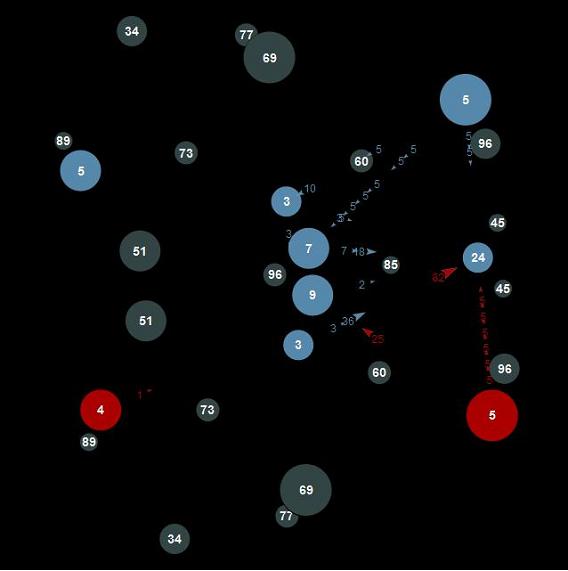

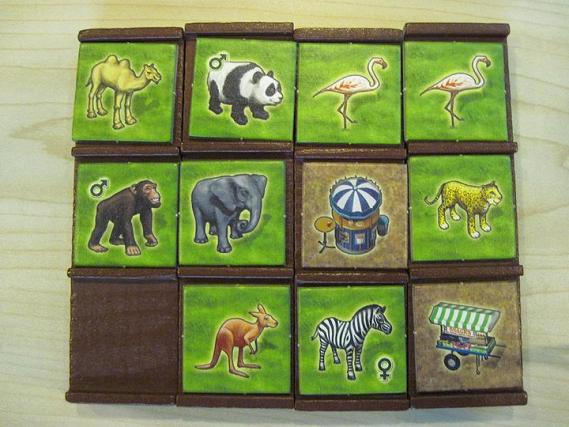

- It’s effectively a very random game and what strategy exists is pretty shallow and obvious. It’s still a lot of fun in the way that waiting to see the results of a die roll is always tense and exciting. The core of the game is about how far you’re willing to push your luck. Do you take a single animal that you need right away or gamble that more of what you need will turn up later, unburdened by tiles that are useless to you?

- This is also a game about screwing over your opponents, so it might go down badly with players who are easily offended. You can pick a truck on the turn that you decide to draw a tile, so you’re forced to put the tile on in the most disadvantageous way possible for the players after you. So instead of thinking how best you can help yourself, you spend most of your time in this game thinking about how you can hurt your opponents the most. Very nasty.

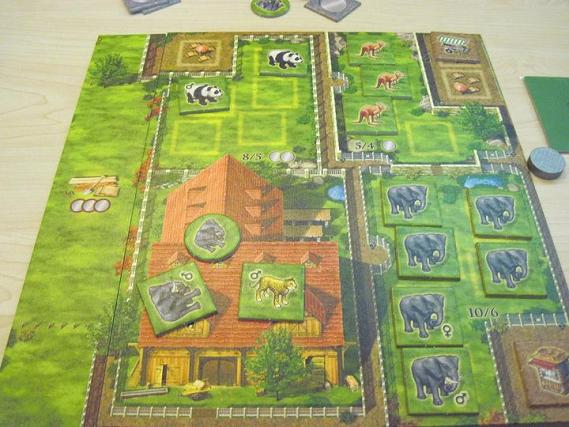

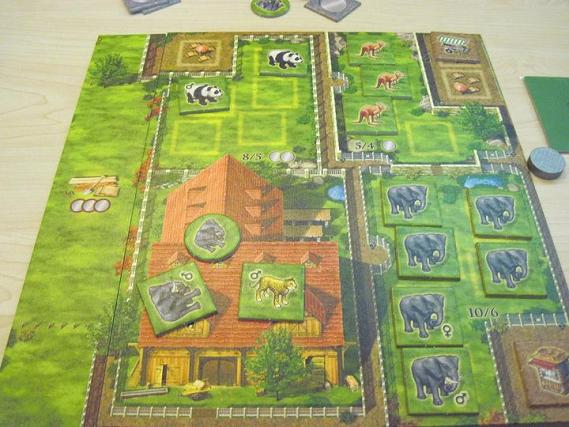

- One important difference from Coloretto is that you have to decide which enclosure you want to store your animals in, which is equivalent to declaring in advance how many of that type of tile you intend to collect. Obviously, you’d want to put animals that no one else has started collecting in a big enclosure, and put animals that you’re going to have to share with other players in a smaller one.

- I was surprised to see how important the snack stands and money tiles are. They’re universally useful to everyone, by contrast to the normal animal tiles can be very useful to the right players and very bad for others. So implementing them in this way seems to spoil the elegance of the game a bit.

Overall, I find this to be a lightweight game that’s okay in small doses but would likely boring quickly. I suppose it’ll always be good as a game to play with kids. I still like this more than Coloretto because it’s fun to play with more bits, but I concede that it’s hard to justify the price and quantity of components needed for this level of complexity.

As a final note, I was originally interested in this because I find that I quite like the “tycoon” style themes in which each player has build something up on his or her own player mat. Examples might be Agricola, Vegas Showdown, Shipyard as reviewed by Hiew etc. When I suggested the movie studio theme Hiew said that this already existed in the form of Reiner Knizia’s Dream Factory and Allen suggested Restaurant Row as another obvious example of the genre. Sadly, Zooloretto doesn’t really have any management mechanics so it doesn’t belong in the genre so I contend that a good zoo management game has yet to be made.

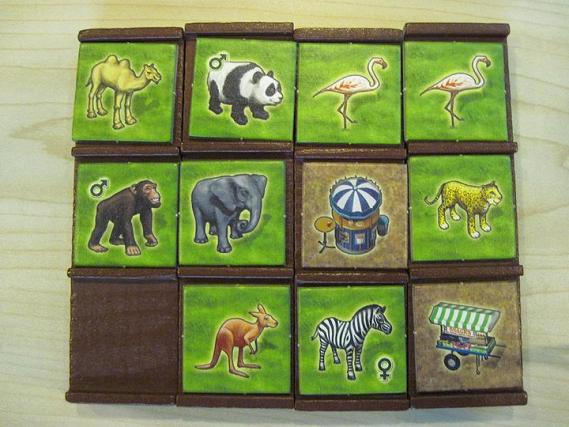

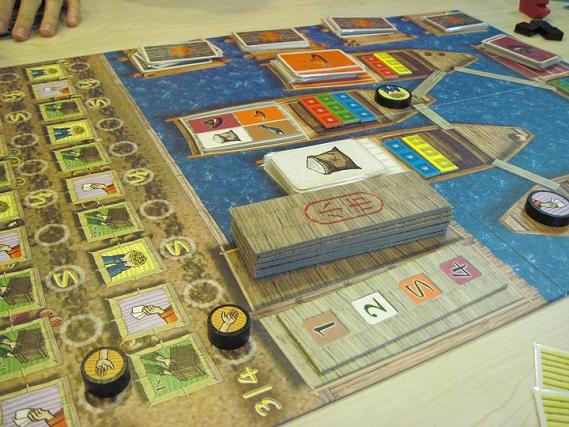

Truckloads of animals waiting for a new home. But wait, why are there food stands on the trucks as well? Ok, that doesn’t make much sense but never mind.