As I’ve mentioned before, I tend to do very badly in area majority games. As these games are played on a map, the positioning of the various playing pieces relative to each other becomes very important. Usually, you need to strike a balance between occupying areas to score points, denying points to opponents and putting your pieces in a better position for future rounds. Due to the many different possibilities, working out the best course of action at any given time can be very computationally intensive. Having the ability to efficiently process visual information helps a lot, and the people I play with regularly can attest to the fact that I’m terrible at this.

This doesn’t stop me from admiring their designs and it strikes me that China is one of the simplest, most elegant designs I’ve played in a while. Its rules take so little time to explain that you might mistake it for gateway game but in actual play, the strategy turns out to be shockingly deep. My thoughts:

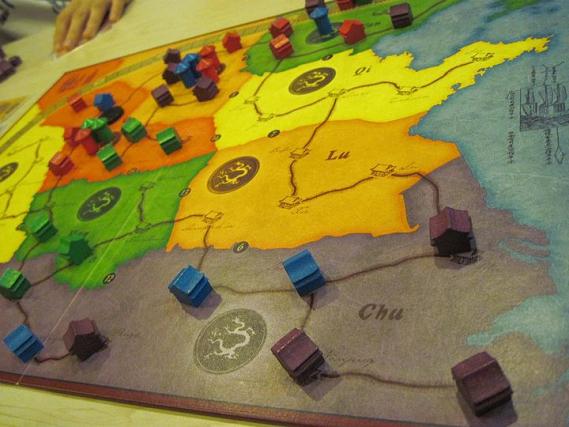

- China has at least a couple of important simplifications compared to the other area majority games I’ve played. I’m thinking mainly of El Grande here, but it should also apply to games like Tikal and Louis XIV. First, once you put a house down somewhere, you can’t move it elsewhere again. This means that when you invest in a province, it must be for its own sake as there’s no value in putting your tokens in a strategy location with a view towards moving them when the opportunity occurs.

- Secondly, the cities along the road system limits the total number of houses that can be played in each province, eliminating situations in which two players continually pile every increasing numbers of tokens in a key area to win it. In fact, if you have the right cards, it’s pretty easy to guarantee a majority in any given province. The problem is the opportunity cost of not investing in other places.

- These two changes make it a lot easier to quickly evaluate the value of various possible moves. This might result in less depth but China makes up for it in few other ways. First, the scoring system is ingenious. Once a province is full, however has majority gains points equal to the total number of houses in it. The next player then gets points equal to the number of houses placed by the first player and so forth. In case of ties, all players get the full value of the points earned. This effectively encourages players to sort of cooperate as no one has an interest in completely filling out a province all by himself.

- The second way to score is by placing emissaries. This is a more risky move as only the player with a majority of emissaries may score points and you need a majority in both provinces which share a border. When it does work however, you can potentially get a lot of points relative to tokens placed. This is because the maximum of emissaries that can be placed in a province is equal to the number of houses that the majority player owns there, so a majority of emissaries is a lot easier to achieve.

- Finally, you can also score points by building a string of at least four connected houses. This turned out to be pretty hard to achieve as players are constantly looking for ways to block each other.

- Going first turns out to be a disadvantage here as if you’re the first to place a house in a province, you can only place one, giving the next player an opportunity to place two houses in there. If there are two players after you who are able to place two houses each, you’re basically screwed. In our game, this made everyone very reluctant to be the trailblazer in a new province. I suppose players can account for this by keeping track of which cards opponents pick up but it’s pretty tough. When we played with the Grenzstreitigkeiten expansion map, this wasn’t a problem as there are border towns which count as belonging to two provinces and Chee Wee happily snapped these up quickly.

- Both maps we played seemed very finely balanced between the various scoring methods. In our second game, I made a conscious decision to ignore emissaries as there was intense competition for them and still did okay. Instead, I went for the port towns, which collectively act as an extra province. This is a very subtle game however and I hesitate to say more without considerably more experience. Overall, I thought it was a great game with an extremely impressive design. I certainly found it much easier to understand that other area majority games.

- The theme of course doesn’t matter at all and it is a bit of disappointment if you were actually expecting something based on China. I find myself not minding as much as many other games however because of how abstract and simple the mechanics here are. It would be like trying to complain about Chess or Go not being thematic.

One Response to “China”

Trackbacks

Leave a Reply