Considering that this game has a 2002 release date, it’s perplexing how little attention this game has on BGG, judging by the number of posts in its forum. Perhaps it’s because it doesn’t yet have an English version? Interestingly as it was also designed by Michael Schacht who we have to thank for the excellent China, this game has a Chinese theme as well. Here, the players seem to take on the roles of merchants who are trading on the junk-based floating markets of Asia. The object of the game is simply to earn the most money possible.

Personally, I had a hard time learning this game. It’s abstract, yes, but at least in something like China, it’s possible to imagine what the pieces and situations might correlate to in the real world. Here, it’s pretty hard to figure out it is that you’re supposedly doing beyond playing a game with some pretty arbitrary rules. I know that technically this is true for all games, but I find it much easier to understand what’s going on if your actions and roles actually make some sort of real-world sense.

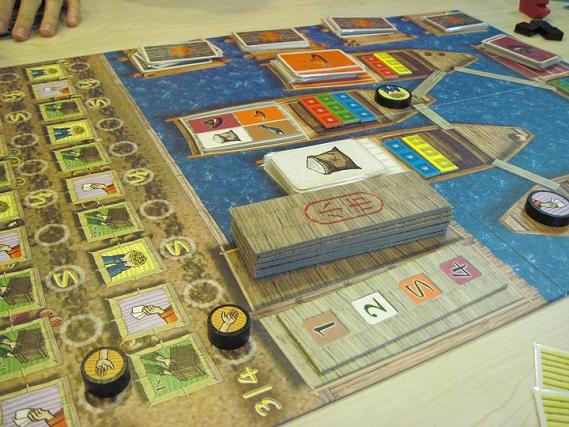

The main area of the board depicts five junks connected to each other by gangplanks. Each player can load these junks up with crates of their own color. I suppose that the cool innovation for this game is that these crates are represented by a strip of three crates and the storage area on the junks are a 3 x 3 area. So if you have two of such strips in that area and no one else has any, you’d have six visible crates on that junk. But what happens if another player comes along and places two of his own strips there? The first one would fill out the remaining empty space of course, but the next one would then be placed on top of the other strips laterally. It would then cover one crate from each of the three strips underneath it, so that the old color would have four visible crates and the new one would have five. It’s a pretty neat conceit.

Furthermore, at all times, three action tokens are distributed among the five junks in a predetermined setup. Each token represents a specific action associated with the junk it is currently on. Every turn, the tokens are rotated clockwise so that they end up on different junks. You’d notice that two of the junks won’t have tokens on them. Instead, at the top of the board are two rows of actions. The game is played over a fixed ten rounds, so this track serves both to keep track of the current round and to signify what the extra two actions for that round are. The first player to take one of these actions chooses one of the two free junks to associate it with and the next one is forced to choose the remaining free junk.

Each junk also has a deck of goods cards on it, so that there are five colors of goods in all. At the beginning of each turn, a card is turned over to determine how much each type of good is worth during that turn. So one color is worth 4 Yuan, another 3 Yuan and so forth. One last color yields not money at all, but special cards, of which there is a large variety, but more on these later. During a game turn, the players have three things to do. First, according to turn order, they pick an action to perform. There are basically only three possible actions. One, is to collect Yuan equal to the number of visible crates of your color on the junk the action is currently associated with. Two, is to collect goods cards from the junk, again equal to your visible crates. The last action is to place strips of goods onto the junk.

Once that’s done, everyone gets to collect two goods cards of whatever color they want. Finally comes the dreaded blind bidding part. Each player chooses the goods tiles that he’s offering secretly and everyone exposes their selections at the same time. Offers are eligible only if the cards are all of a single color. If a player selects cards of multiple colors in a bid, it’s considered a bluff and the player gets to take them back. All cards used in real bids are lost and the prizes go to whichever player offered the most goods cards of the respective color. This auction takes place as many times as necessary until all five prizes in each round is claimed by someone. Then the round ends, the action tokens on the junks are rotated and a new round begins.

The special cards I’d mentioned earlier come in too much variety to describe completely. Some are used to gain goods cards or money. Some other give a nifty ability, like being able to break ties in blind bids. But probably the most significant of these are the bonus point cards which give you Yuan for having a certain number of visible crates on specific junks at the end of the game. The main way of getting these cards is the auction that happens every round but all players have a chance to grab them at specific points in the game. Drawing these cards work differently than most other games however. You choose one of the decks of such cards, look through the entire deck and pick one to keep. So if you find a deck with a few cards you’d like, you might want to keep coming back to it, but memorizing everything that you’ve seen becomes a bit of a chore.

And that’s it for the game’s mechanics. It’s not really very difficult but the disconnect between the various concepts make it hard to take in. The auction for example is clearly supposed to be the most important phase of the game, but the Yuan gains from it often seem insignificant compared to taking the money action, which doesn’t require giving up any goods and has no uncertainty at all. In our game, collecting between 5 to 9 Yuan for taking the money action was quite common, making a mockery of the top 4 Yuan reward in the auction. It doesn’t help that I’m not a fan of blind bidding mechanics which I think mostly amounts to guesswork.

Other than the blind bids, there’s very little chaos in the game. In fact, if you’re up to it, it is in theory possible to work out far in advance which junks the action tokens will be for every turn. As the two extra actions available each round is known in advance as well, you could set up some nifty combos by placing goods crates on the right junks and then pulling in massive profits in coin and goods when the right action tokens move onto them. But beyond the next couple of turns or so, that’s an insane level of planning that would take a horrendous amount of time to work out.

Quite surprisingly for everyone including myself, I won our game because I manage to fulfill the conditions of three bonus cards at the end of the game, which were in total worth 28 Yuan. That’s nearly half of my total Yuan for the whole game. Now, I expected to gain those points but I still didn’t expect to win because I was trailing everyone in Yuan and thought everyone else also had these bonus points. In the end, it turned out that only Shan and me had managed to score them. I suppose that I had been lucky in picking out the right three cards and had been astute in ensuring that the requisite number of crates were visible on the right junks, but I still think that it’s a bit ridiculous that a single hidden move like this won me the game. It’d have been different if the other players could see it coming and worked to prevent it from working, but as the rules are written, it’s an unpredictable end of game element that no one can plan for.

Overall I find Dschunke to be a pretty mediocre game. It has some nice ideas but I don’t like the scoring system and how the availability of the actions on the different junks are in theory perfectly predictable from the first turn. I also think that the various systems don’t gel together very well. The system of having players pick any two goods cards every turn, for example, feels particularly uninspired, as if the designer think of a more interesting way to replenish the players’ supply of goods cards that tied in more closely with picking actions. I’m not even sure what’s up with the silly paper Yuan that are used only to keep scores. It seems the designer thinks it’s important for scores to be secret, but then players have to declare their Yuan count at two specific points in the game, one of which is in the penultimate turn. It’s a very strange design decision to me.

Leave a Reply