Now that I’ve left Kota Kinabalu, this will probably will the last post I write about boardgames for a while. On our final visit to CarcaSean, we played Piece o’ Cake, which Sean prefers to call by the literal English translation of its German name, “… but please, with whipped cream“, San Marco, which seems to have been an inspiration for Piece o’ Cake and Alhambra. The last of these is too well known for me to meaningfully write about, so I’m just jot down some observations of the former two games.

Both of them are pie division games, in which the active player must choose to divide resources into different piles while knowing that he will be the last person to get to choose one of the piles. In the case of San Marco, the resources to be divided are good cards that permit the owner actions plus bad cards. Accumulate too many of these and your turn ends early, potentially giving the other players an extra turn of actions plus bonus points. In the case of Piece o’ Cake, you literally have to divide pieces of cake into portions to be distributed among the players. It’s a very neat game mechanic that I’ve never encountered before this.

- Piece o’ Cake wins extra points from me for being a solid game despite having nothing but slices of cardboard pies as its components. Even the points value for eating a slice is directly indicated by the dollops of whipped cream on it and you record that simply by turning your slice over. If you choose to keep a slice, its points value is indicated as a number on the slice itself, which also equates to how many slices of it are in the game. At the end of the game, you need to have a majority of that type of cake for these points to be counted. What a wonderfully minimalist design!

- Eating the slices immediately for the whipped cream points is actually more lucrative than I realized at first, and a good way to discourage people from making overly large portions for other players to choose. Often, the player in charge of dividing the cake will attempt to break up the pieces of the same type of cake to prevent one player from easily getting a majority of it, but this may result in very skewed portions.

- Despite this, I won the game by going with the majority strategy instead of eating pies. I had by far the least number of points due to eating but made up for it by having a commanding lead in the high-valued cakes. Strangely, just having two slices of the same cake was enough most of the time to dissuade Shan and Sean from competing with me for the majority as they opted to eat their slices instead of risking them being worth nothing.

- I enjoyed the game a great deal more than I expected. It’s hard to dislike a game with such an intuitive premise and so easily explained rules that can nevertheless yield the frustrating decisions that make playing boardgames so enjoyable. I do note that towards the end of the game, it became easy to predict how each player was going to divide the portions since it is quite straightforward to deduce what each player will want to take. This makes the final round more of an exercise of playing out the inevitable instead of something that involves real decision-making. Thankfully, the game is short enough that it isn’t a big problem.

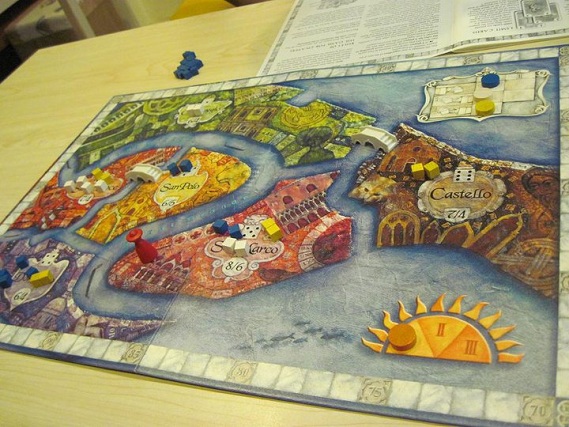

San Marco is quite a bit more complex, combining the now familiar area majority mechanic with pie division. Here, players place their markers in the various quarters of the city and earn points by having the majority of markers in a quarter or coming in second place. The twist is that players have no fixed actions each turn. Instead, a set of action cards are drawn and one player must split these action cards into different sets to be distributed among the players, again with the player deciding on the split being always the last person to get his set of cards. In addition, there are also bad cards that are also distributed into the sets. This means that the player doing the distribution must take care to balance good action cards with enough bad cards.

- The relative power of the action cards are wildly unbalanced. One type of card for example, merely allows you to move one of your markers from one quarter to an adjacent one, provided that you already own a bridge connecting the two quarters. Another card lets you choose any quarter and turn any one of your opponents’ markers there into one of your own. Yet another one allows you to choose a quarter and then roll a six-sided die. You then remove the indicated number of markers from that area. But the great thing about pie division is that it’s up to the players to balance the sets themselves using a combination of good and bad cards.

- As usual points for all the city quarters are tabulated once at the end of the game, but over the course of the game, points are only awarded when the Doge card is played. This allows the player to move the Doge marker to an adjacent quarter and score it. Naturally, players will want to move the Doge to where they have the majority. In our game, the Doge card barely appeared at all for most of the game and most of our scoring took place in the final phase of the game, rendering some of the early game maneuvering a bit meaningless.

- I noticed in this game that coming in second place in a quarter yields only slightly less points than being first and managed to achieve a second place position in almost all quarters. Shan and Sean noticed me doing this and tried to stop me, but I managed to keep it up and eventually won the game. I rarely win games against Sean so it’s quite funny that I should win two games in a row on my final visit to CarcaSean.

- Another thing is that there is no secret information at all in the game, so you could theoretically keep a running count of everyone’s scores in your head. This would be very useful if you needed to know whether you’d be better off trying to score more points or taking away points from a particular opponent. Actually doing this would be time-consuming and a bit dodgy, so I refrained and counted it as a mark against the game. In Piece o’ Cake, cake slices you choose to eat are hidden from other players, preventing just this sort of thing.

- Due to the complexity of the action cards and the counterbalancing effects of the bad cards, dividing them into sets is far more excruciating than in Piece o’ Cake. Arguably this is the meat of the game itself, as choosing which set to go for and how to use the cards in the set you get are relatively straightforward decisions. I did a very bad job at this at first, making sets that were too extreme such as many good cards and many bad cards in the same set. This tended to come back and hurt me when people wouldn’t take the set with the bad cards, no matter how good the actions cards in it were. Sean tended to try to get each set as balanced as possible and I copied him later.

- I’m normally not a stickler for such things as dice being properly balanced in games, but I got annoyed when I rolled nothing but 1s and 2s in this game whenever I played the Banishment card which lets you remove markers from a quarter. Shan swears that the wooden dice used aren’t fair and always result in 1s far too often than random chance dictates. Perhaps I should start insisting that properly certified dice be used in all games that call for dice.

Both are good games that uses a game mechanic that is novel to me. Piece o’ Cake impresses me more for how much it manages to do with so little but San Marco is probably the better game for the long haul.

Leave a Reply