Just as we are flush from our success in subduing the warlords of Yunnan, the Japanese surprise us by mounting a second amphibious assault at the exact same location behind our lines. Though this force of six combat divisions is notably weaker than the first one, most of our spare units are deployed in the south of the country. We are forced to deploy reserve militia units to contain the threat. It takes three weeks for us to surround and completely destroy the invaders.

The next several months pass quietly. Our aggressive expansion of our merchant marine fleet means that despite the continuing blockade, our flow of raw resources remains uninterrupted. Our concern at the moment is that our success is causing the other nations to fear us. Though we are now ideologically aligned with the Allies, we are not invited into the alliance, due to our war with Japan, but also because of the threat we are perceived to pose. Even countries as far afield as Australia and New Zealand view us as the most dangerous threat to world peace.

But we will not allow this to restrain our ambition to unite all of China. Our plans for war against the warlords of the Guangxi Clique will require many units to be deployed in the south. Accordingly, in March 1939, we embark on a plan to make these units available by shortening the frontlines against the Japanese in the north. Rather than attempt any risky breakthroughs or encirclement maneuvers, we elect to simply apply constant and irresistible pressure to the very western end of the Japanese lines at the borders of Xibei San Ma.

By May 1939, this results in the Japanese lines being pushed eastwards until the other side of the Yellow River system. With the river separating the two sides on every point along the line, it will be very difficult for the Japanese to mount an attack. Even allowing for considerable reserves behind the lines to guard against misfortune or unexpected upsets, this maneuver frees up two corps of soldiers which we send to the south. Of course, this also means that it will be much harder for us to act as well when the time comes for us to make our move against the Japanese.

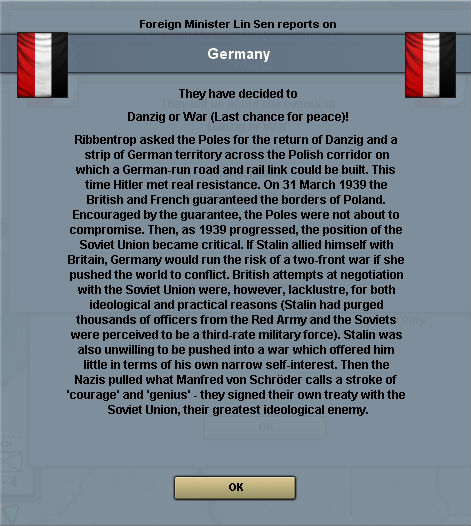

In August 1939, while we are still finalizing our preparations for the subjugation of the Guangxi Clique, war breaks out in Europe as expected. Germany’s invasion of Poland is answered with declarations of war from France and the United Kingdom who have both guaranteed the independence of Poland. Embroiled as we are in our own war and not being a member of any of the major factions, we have little direct information on these events. Nonetheless, it may be surmised that the fighting is fierce.

In September 1939, with no further activity on the northern front detected, we begin our own assault against the Guangxi Clique. The clique controls a total of four vital provinces that we must seize if we are to break their will to fight. Three of these territories are near their border to us and can be taken relatively easily. We assign one corps of infantry to each of these provinces. The final province is the capital of Guangzhou itself which is located within their interior. No less than three corps of infantry is assigned to this single objective, supported by an additional corps of militia units. In addition, six divisions of garrison units are on hand to guard our own borders and to rapidly move in to occupy the key provinces once they have been conquered.

Instead of spreading our forces in a line to meet the Guangxi defenders as we have done in the north with the Japanese, we elect to concentrate our forces to attempt to blitz through to the capital so as to end this war as quickly as possible. Indeed, under our plan, several divisions of Guangxi infantry are allowed to advance northwards into our territory completely unopposed. We are betting that we can take their capital and force their capitulation before their forces can travel far enough to be a serious threat.

By 9th October 1939, the corps assigned to the three border provinces have long since taken their objectives, despite taking more time than expected to occupy them due to the difficulty of traversing the mountainous terrain. This prevents them from cutting eastwards to lend their support. The other forces reach the outskirts of Guangzhou but one corps of mountain troops finds itself completely surrounded and cut off. Such is the risk of blitzing in without properly covering the flanks. Our single wing of tactical bombers is occasionally called in to provide support in the toughest battles but its World War I-era technology quickly becomes evident when it forced to break off after only a few bombing runs.

But as Guangzhou falls just three days later, the entrapped corps is spared any serious harm and all resistance collapses. We annex their territory and add them to the resurgent Republic of China. Such is the wealth of the region’s natural and intellectual resources that this addition makes us more than a match for the Empire of Japan. The boost to our industrial base allows us for the first time to envision building a navy and an air force that is actually worthy of the name, assuming that we can buy or develop the required technology. Controlling Guangzhou also allows us to trade directly with Portuguese-controlled Macau and British-controlled Hong Kong, bypassing the Japanese blockade.

One day after our own victory, we hear the news that Germany has annexed Poland, though its government refuses to surrender and choose to fight on. It appears that the so-called Allies are not faring too well in their own war in Europe. For our own part, victory over Japan is now a matter of when, not if, and we must plan beyond even that. Do we confront the Soviet Union and demand the return of Sinkiang? If so, we must begin building a powerful tank army. Or do we take advantage of the Allies’ weakness and take back Hong Kong and Macau that are rightfully ours? This would require a large and modern navy. There is much to think about.

Leave a Reply