We arranged a special gaming session on a public holiday here in Malaysia to play Die Macher in expectation of its long playing time and Sean even asked everyone to watch the Board Games with Scott video tutorial beforehand. Surprisingly, everyone complied, more or less, and we managed to finish what we expected to be a five hour plus game in under four hours. That still sounds pretty daunting and I believe that Die Macher has the highest average game weight of any game I’ve played so far on BGG, but everything went very smoothly and contrary to my initial fears, everyone was fully engaged in the game and had lots of fun.

I’ve never played anything like it so I have no idea how to categorize this game. The idea is to simulate a series of regional elections in Germany with each player controlling one of the political parties involved. Every player tries to influence the elections through a variety of actions, such as placing Media Markers in regions, organizing meetings, and sending the members of their Shadow Cabinet to key regions. Campaigning costs money of course, so players must manage their limited resources. At the end of the seven elections, the results for each player are added together to see who is the overall winner.

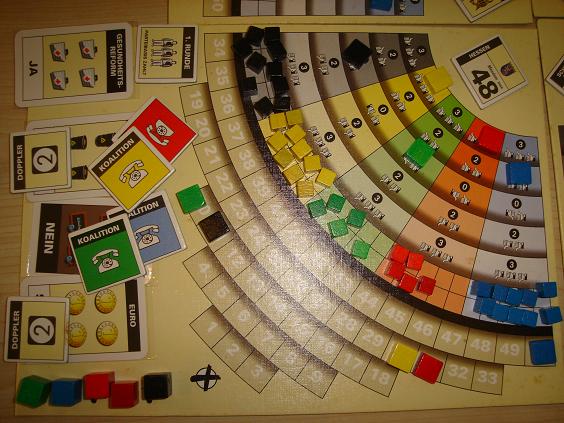

What’s interesting about this game is that while there are seven elections in total and one regional election is resolved at the end of each round, there are four elections in play at any one time. This means that you can devote resources to improve your position in elections that will take place in the future. Furthermore, where each election is going to be held is randomized by drawing tiles for them when the appropriate election board is set up. Since some regions are worth more seats than others, it’s easy to see why players might want to give up on some regions to focus on others.

The other point of interest is that each round is broken up into a number of phases and only one specific type of action is allowed within a phase. This starts with the Party Platform Conference during which players can take turns to exchange one of their face-up Party Policy Cards, representing how their party feels about specific issues. This is then followed by the Shadow Cabinet phase where players decide whether to play any of their Shadow Cabinet cards and which region to play them in, the Media Markers phase where players buy media influence in the regions and the Party Meetings phase which involves putting down meeting markers in regions that can be cashed in to be turned into votes.

The final phase before the actual election is the auction for the Opinion Poll cards which introduces a bit of randomness to the game. Whoever bids the highest gets the card which only the winner gets to see and decide to publish or not. Publishing it means adjusting the Popularity Ratings for two parties as given on the card while not publishing it allows the winning bidder to increase his or her party base. Naturally, at the beginning of the game when money is tight, these cards are won with very little money but towards the end when everyone is flush with cash and because unspent money is worthless at the end of the game, players are willing to drive the prices for these cards to stratospheric heights if only to keep them out of the hands of other players.

Breaking up each round into so many phases is interesting because while it understandably makes the game harder to learn (even Sean had to constantly refer to the rules to remember the sequence of the phases), it also ensures that there is virtually no downtime for any player. Even if only to decline something, every player has a decision to make during each phase and every player has an interest to take note of what the other players are doing. As Scott Nicholson who made the tutorial video we used noted, it may be a long game but everyone is so constantly involved in everything that is going on that the time just flies past.

All of the actions in the preceding phases come together during the election at the end of each round. All of the meeting markers each party has in the region is converted to votes with the efficiency of the conversion being determined by a combination of the party’s local popularity and how closely the party’s policies converge with the preferences of the voters. The player with the most media markers in the region is deemed to have media control there and is able to influence the voters’ preferences there. Naturally whoever has the most votes wins the election but as a twist, there is a fixed upper limit to the maximum number of votes possible. This means that multiple parties will likely get the maximum number of votes and the winner is the party that was last to hit that magic number.

However actually winning an election has only limited benefits as it entails only being entitled to place a Media Marker on the national board and being able to influence the voters’ preferences on the national level. Every player still gets points in proportion to the votes earned, which means that every player who achieves the maximum number of votes gets the full value of the region’s victory points even if he didn’t win the election. This was what happened in our game as Sean actually lost most of the elections but still earned enough points to win the overall game.

Some of the design choices don’t make sense within the context. For example, turning down campaign contributions from interest groups increases your party membership while accepting them decreases it as presumably supporters become upset at your party for selling out. On the other hand, the players are allowed to change their party’s policies without repercussions which is odd as one would expect that the party faithful would punish flip-flopping over key issues more than accepting cash.

Personally I would have preferred it if the players had more flexibility over choosing what their party policies would be but would be heavily punished if they changed policies often, especially when moving from one position to its diametrical opposite. In our game while all of us started with different sets of policies, we gradually all converged towards the same values by the end of the game. The sole exception was my wife. She led the early game by a hefty margin but as everyone changed their party policy, she couldn’t draw the necessary cards to change hers in response and so ended up in last place.

Still, the end result of all this is an undeniably deep strategy game that is actually more approachable and intuitive than its rules would suggest. I can’t see playing this game too often due to its length and the need for dedicated players, but as Sean says, it’s something that every boardgame player needs to play at least once in his or her lifetime. I think that a game with experienced players would play very differently indeed as one learns how to manage cash better and realize how important it is to manipulate the turn order.

Finally, no discussion about Die Macher would be complete without mentioning its age, as it was first released in 1986, and the fact that it’s the first boardgame entered into the BGG database. Sean told me that the game wasn’t really a success when it was first released and implied that it only acquired its reputation as the granddaddy of Eurogames after Settlers of Catan sparked off the explosion of the hobby in the mid 1990s. As such I think it can be fairly said to be a game that was ahead of its time.

5 Responses to “Die Macher”

this is a very nice game, can’t really feel time’s passing~

hope to play this again ^^

I read a number of topics. I respect your work and added blog to favorites.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts about carcasean. Regards

my weblog … different training game (Luz)

Trackbacks

Leave a Reply