I must admit that I may be biased because Sean’s German-language version of this game made it something of a pain to learn, but I found little to like about Scepter of Zavandor. Trying to remember what all of the different ability tracks do was a real chore. This is actually a bit odd as it has all the hallmarks of a standard Euro game and even bears some resemblance to Goa, which I really liked. But for a variety of reasons, I only got progressively more annoyed with the game as it went on.

First, there’s the theme. While it was initially intriguing to see fantasy fare in a euro game, I was eventually put off by it as there’s nothing magical about the rules at all. It’s not just American high fantasy either. The art, choice of characters and general feel places it closer to dark European fantasy. Think Brothers Grimm instead of Tolkien’s Middle Earth. The backstory is ostensibly about a group of magic wielding characters racing to gather enough magical energy to somehow obtain or unlock a set of powerful artifacts. They do this by collecting sets of gems that generate magical power and then spending that energy to obtain better gems and magic items. In practice, all this ends up being one of the most naked engine-building games I’ve seen and the theme soon becomes a distraction.

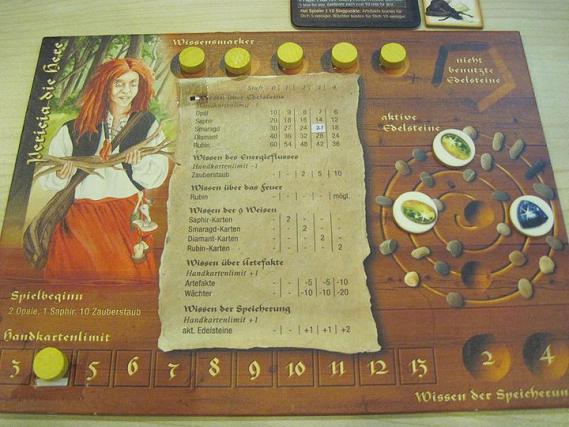

Each player is given a mat that tracks the number and type of gems he has. The lowest grade of gem, the opal, only produces magic dust of various fixed denominations, but the other gems allow to draw a card of the appropriate type that gives you a variable amount of magical energy to spend. Naturally, the better the gem, the more magical energy the corresponding cards provide. Collect a set of four of the same type of gems however and instead of drawing a card, you get a concentrated energy token of the corresponding denomination to spend. All of this magical energy is basically still fungible currency that you spend to perform actions and buy things so having it take so many different forms was the second reason why this game annoyed me.

If all that wasn’t complicated enough, there’s also the rule that there’s a limit to how much magical energy a player can bring forward each round. This is represented by something that is absurdly translated as a hand limit. With all of the different forms the magical energy in the game takes, each uses up a different amount of this capacity. Excess energy beyond this limit must be discarded, giving players a strong incentive to spend all that they have available. As the cards for the various gems tend to have odd values, adding up all of your magical energy every turn and working out how to spend it most efficiently and not have to discard any at the end of the turn is a tiresome affair.

During his turn, each player has a number of things to do in any order. One is to start an auction for one of the magic items or artifacts available for purchase. There is a number of magic items that are available every turn equal to the number of players in the game. Typically these provide some victory points, some sort of benefit, such as increasing your hand size or acting as a certain type of gem for example and many also provide a discount when buying a specific other magic item that appears later. The artifacts all provide victory points only and the game ends when a certain number of them have been bought. Both the items and artifacts have reserve values that determine at what price the auction must start, but after that it’s up to the players to bid however much they want for them.

The second type of action is to buy gems. Initially players are only allowed to buy opals and sapphires and are only allowed to buy emeralds and diamonds once they own the appropriate magic items. The most powerful gem is the ruby which can only be bought once the player has reached the end of one of the knowledge tracks. Again, the more powerful the gem, the more expensive it is. Each player has a limited number of spaces to put gems in so you can’t build an income stream just by buying many multiples of the cheapest gems.

along the knowledge tracks.

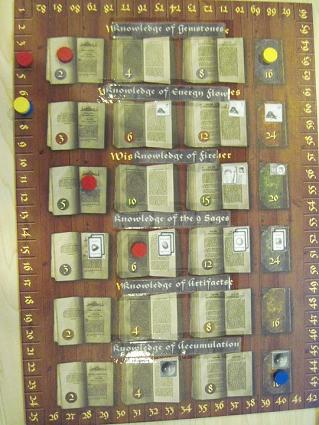

The last type of action is to advance one space along one of the knowledge tracks. These tracks act much like technology trees in other games, conferring various advantages as you move up them. The Knowledge of Gems track for example, gives you increasing levels of discounts for buying gems. As previously mentioned, rubies can only be bought once you’ve reached the end of the Knowledge of Fire track, so there’s no advantage to be had until that point. Each level of advancement gets progressively more expensive as is the norm but if you have yet to have a token along a path, you also need to pay extra to free up a token to make it available, and that gets very expensive as well.

Having each player control a different character with unique differences is a nice touch that I normally appreciate. I really like game designs with asymmetric sides. Here, different characters start off along different tracks and their starting amount of dust and hand size is varied at all. In the case of Scepter of Zavandor however, all of us ended up playing more or less the same way after the first few rounds. Whether that’s just how the game plays or because we’re unfamiliar with the game’s strategy, I can’t say.

Finally, scoring is based on what you have every turn. You get points for magic items and artifacts as already mentioned. But you also get assessed for having gems and reaching the end of knowledge tracks. The score aren’t cumulative so you would lose points if you lost a gem for some reason. Scores are also important in that they determine turn order. The player with the current highest score goes first and the one with the lowest score goes last. There’s no advantage to going first in Scepter of Zavandor and plenty of advantages to going later so this can be seen as a sort of catch up mechanism. Players going first need to pay more for items and artifacts they win at auction while players going later get a discount. Also quite significant is the ability to start an auction later in the round once other players have already spent nearly all of their energy doing their actions.

All this is quite straightforward but the whole thing plays too mechanistically for me. I found that I spent most of time fiddling with the weird currency the game uses (Sean brought in a calculator to help out) instead of making interesting decisions about what to buy and which knowledge track to advance along. Even the auctions were uneventful until the final couple of rounds when everyone could finally afford the expensive artifacts. Many rounds went by without anything being bought and when someone did want something, there was not much fighting over it. Despite the different forms it takes, the game only has one type of resource so there’s no need to balance production of one resource against another. You just try to get as much magical energy income per round as possible in the most direct way.

That many euro games have rules that are completely out of whack with their subject matter is nothing new but I’d say the discrepancy is much more painful here. I’d expect something that’s so heavy on the calculation side in a game with an industrial or economic theme, but in a game with a fantasy theme? It doesn’t help either than this is a game of open information and no surprises. You’d expect a game about magic to have more of a twist and some suspense, but it’s a brute engine building game all the way through. You don’t even need to make hard decisions such as whether to go for points now or to delay gratification in order to optimize your income generating machine further as the two are so tightly correlated.

Anyway, a brief look around BGG reveals that this game has its share of fans so there might something that I’m missing in all this, but for my part, I don’t like this game at all. If it were shorter, I’d be willing to cut it some slack, but it’s so long and so heavy for what it offers that I don’t really see the point at all when there so many much better alternatives available.

One Response to “Scepter of Zavandor”

Trackbacks

Leave a Reply