We played In the Year of the Dragon some time back, but as we made a critical error during our session, I’ve been reluctant to write anything about it. Since then, I’ve spent some time toying around with the flash version of the game so here are some of my thoughts. In this game, the players take on the role of rulers of ancient China who must each guide their respective realms through an eventful year. Oddly however, while dragon years are generally considered auspicious ones to the Chinese, the year that this game covers is a decidedly tumultuous one.

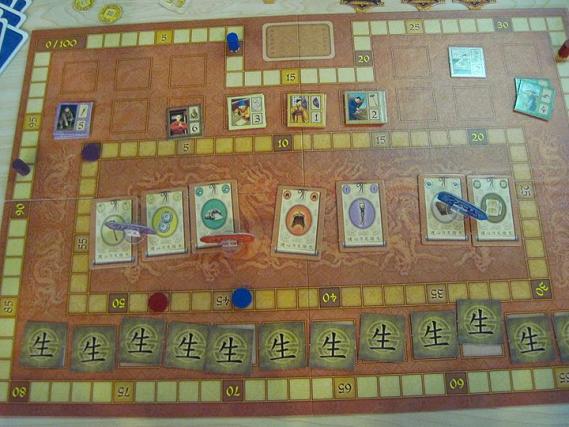

In the Year of the Dragon has deceptively simple rules. The game is played across a total of twelve rounds with each round representing one month of the year. Each player starts the game by choosing two skilled persons to come under his or her employ but the game imposes a rather devious restriction of not allowing players to take the same combination of persons. Each player is also given an identical set of cards allowing him to hire one person of each of the nine different types plus two wild cards which can be used to hire any person. Thus set up, the players do only two things every round. First, they select an action to perform according to the player turn order. Second, they play a card from their hand to employ a new person. After that the event for the current month is resolved, the scores updated, and then it’s on to the next round and the next month.

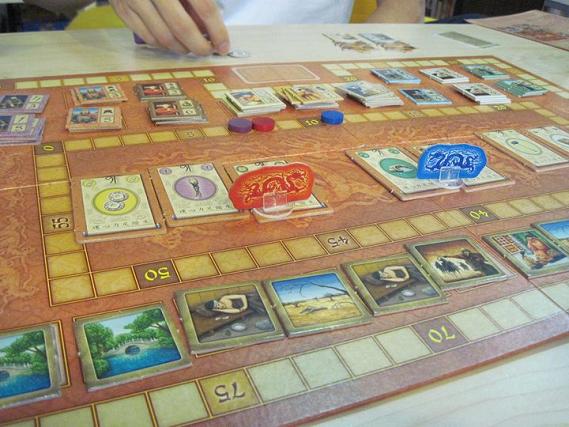

In total, this means that each player has exactly twelve actions to perform and eleven hiring decisions to make over the course of the entire game. The available actions are all about different ways to gain points and most importantly, to survive the year. Each month is defined by a different tile, of which there are a total of six different types. The first two months of the year are always peaceful affairs so players have time to set themselves up. The rest of the year is determined by randomizing the event tiles at the beginning of the game. The fireworks event for example is pretty innocuous as it just offers a scoring opportunity to the players with the most fireworks with no consequences if you have none, but the rest of the events can be pretty nasty.

The tribute event for one requires that players pay 4 yuan, the currency used in the game. For each yuan that a player is unable to pay, he must dismiss one of his hired persons. The mongol invasion event is another scoring opportunity for players with the most military power but players with the least are penalized by losing one person each. The most fearful event is probably contagion, which forces players to lose three persons, minus one for each apothecary pestle and mortar they have. This seemingly endless stream of bad news makes the game feel like you’re always fighting just to survive. Some years are worse then others. A sequence of Peace-Peace-Drought-Contagion-Drought is something to be feared indeed.

Crisis management is performed by taking actions to prepare for the various events and hopefully you have the right persons to make your actions more effective. For example, taking the rice action gives you one rice plus one additional rice per rice icon on your farmers. Taking the taxation action gives you two yuan plus three additional yuan for each tax collector you have working for you. One action that all players need to take frequently throughout the game is the building action, which allows you to build one pagoda floor plus one extra floor for each builder you have. You start with two pagodas of two floors each and persons living in them, but as you can recruit a new person every turn, space fills up fast.

This brings us to the final and most critical thing about this game. Most of the available persons come in two versions, a younger and less skilled version or an elder, more skilled one. The young warrior for example provides one warrior helmet but the elder version provides two. So why would you ever hire the young version instead of the elder one? Because the younger ones provide more people points. People points determine player turn order in this game. Your people points total starts accumulating from the first two persons you get at the beginning of the game and every person you hire thereafter adds his points to that total. Whoever has the most people points goes first. If players are tied, the second player to reach that point total goes first.

Turn order is overwhelmingly important in this game because the available action tiles are randomly sorted and distributed into groups equal to the number of players. This part is where we got the rules wrong during our session at CarcaSean. We thought that players execute all of the actions in the group picked. Instead, players only pick one action in any group to execute. Once a player has chosen a group of actions, all other players must pay 3 yuan to choose that group again. Alternatively, a player can simply pass and refill his yuan supply up to 3. Since all players need to pick more or less the same actions to deal with whatever crisis is looming, being first is clearly a huge advantage. Because we got the rules wrong, we had more resources than normally possible and weathered the year better than you’re supposed. After playing the Flash version, I can reassure you that miscalculating your actions is very painful indeed and can result in a chain reaction that can devastate your pagodas and persons.

In addition to the methods outlined above, victory points are also awarded every turn based on how many pagodas you have. At the end of the game, you also earn points corresponding for the number of persons you have left. One important source of points that I’ve learned to appreciate from the Flash version is taking an action to buy privileges. The larger version earns you two points per turn and costs 6 yuan to buy while the smaller one costs half as much but only provides one point a turn. Despite the cost, starting the game with a couple of relatively useless persons just in order to max out your person points to go first and then buying the large privilege as your first action is widely considered a potentially game winning move. Other points earning methods are employing monks you earn you points depending on their skill level multiplied by the number of levels of the pagoda they stay in the end of the game and employing ladies who come in only one version and give you one point every turn.

One thing to note about In the Year of the Dragon is that once everything is set up, this is a game of perfect information. You even get to pick the first two persons you start out with after looking at the sequence of events in the game. (I guess ancient China had some really good fortune tellers.) This makes it possible to get stuck in analysis paralysis despite the relatively simply decisions required. The other thing to note is that it is simply impossible to save everyone, so you need to resign yourself to cutting your losses. This makes it a somewhat depressing and painful game to play. While there’s no direct interaction between players as is norm is such euro games, the race to be in front on the person point track is always tense and seeing someone pick an action group you desperately need but don’t have the yuan to pick yourself is devastating.

Overall, I find In the Year of the Dragon to be another solid euro game, albeit one without any memorable mechanics at all (my wife claims that she no longer remembers how it’s played). The fact that you can lose people feels suspiciously close to death and does make it stand out a bit from that particular crowd. After spending all that time on the Flash version, I’ve noticed that certain patterns predictably recur. For example, the first player always buys two privileges. The second player must then fight hard to be first in turn order and prevent that player from being able to take any actions for free etc. This leads me to wonder whether or not all euro games are so easily analyzed into such relatively simple patterns.

Other problems are that some actions seem much less useful than others. The military parade action in particular doesn’t seem to be very popular and even trying to vie for the points from fireworks seems inefficient. I don’t think taking the lady early and giving up on the person point race completely is viable either. Then again, I could be generalizing too much from a bit of experience with the AI. Anyway, it’s not a game I’d personally buy myself. It’s just a bit too generic for that and it’s rules certainly aren’t amenable to two players. But it is a game with its good points. Inflicting it on completely newbie players would be a very cruel thing to do if you’re into this sort of thing.

One Response to “In the Year of the Dragon”

Trackbacks

Leave a Reply